POLICE SUICIDE -- JUST A “BAD CHOICE?”

We must recognize that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a physical, as well as an emotional

injury.

by

Andy O’Hara, Founder,

Badge of Life Mental Health for Police Officers

Richard L. Levenson, Jr., Psy.D., CTS, Vice Chairman, Badge of Life

Ron Clark, RN, MS, Chairman, Badge of Life

"Suicide is a whispered word, inappropriate for polite company.

Family and friends often pretend they do not hear the word's dread sound even when it is uttered. For suicide is a taboo subject

that stigmatizes not only the victim but the survivors as well." –Earl

Grollman

It was in 1984 that Phil Donahue coined the unfortunate phrase, “Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary

problem.” Joining other empty-minded quotes about suicide as “cowardly,”

“angry” and “vengeful,” Donahue’s comment would show up in every power point, lecture and conversation

about suicide. It would also set the understanding of mental illness and suicide back centuries.

A “solution,” permanent or otherwise, is defined as “finding a specific answer to or way of answering

a problem.” Donahue was, therefore, suggesting that a suicide victim is

rational enough to examine the problem (PTSD and depression), weigh the options (to live or not live), identify the specific

answer (suicide) and put it into play. Suicide, in the mind of the uneducated,

is little more than a simple choice, one made on the veranda on a summer day with a glass of lemonade.

Sadly, this is the way society needs to think of suicide—as “a choice.” We don’t want to think of suicide being caused by the

confusion, pain and desperation of a mental disorder. That would disempower us and force us to look deeper. If it was beyond the victim’s control, we could no longer blame them.

So, it’s all about “bad choices.” The victim of suicide

was in complete control, made a bad decision, kind of like going right or left at the intersection, and made the wrong decision.

This is how stigma begins—by shaming the victim for “screwing it up” and “making the wrong

decision.” If only we had been sitting on the veranda, sipping lemonade

with them when they were going through the “plusses and minuses” of committing suicide, we might have been able

to slip a bit of sound logic into the rational discussion. But the victim didn’t

invite us, damn them—another “bad choice!”

Once they are dead, we shun the family as though they pulled the trigger. No

suicide note in the world will save them from our judgment—we cast them out, children included, from the police family.

When we hold our memorials, we will say, “It was not how they died that made them heroes, it was how they lived.” But inside, we know we’re lying. Of course it’s about the way they died!

Look at Michael Pigott of New York, Aaron Gililland of the California Highway Patrol, Paul McCarthy of the Massachusetts

State Police—all heroes without question.

But they blew it, we say. They allowed the psychological trauma

that hit them during their heroic events to affect them—that’s not allowed to happen, say police chiefs. Not only did they come out of it with PTSD, it drove them to suicide. And we don’t want to hear that! Many a hero lies dead and unrecognized because we failed to understand

the terrible wound that killed them.

Let’s look more closely at this issue of suicide, the myth of choice, and our perception of police suicides.

Are we in the 21st century—or still in the Middle Ages?

POLICE SUICIDES: A 2012 study shows

there are 125 – 145 police minimum of suicides each year in the United States out of 875,000 officers (NSOPS, O'Hara,

Violanti). Of these suicides, a minimum of eleven percent are the result of the

police job itself (Aamodt and Stalnaker, Table 9). Unfortunately, police departments refuse to accept the possibility

that law enforcement work can lead to suicide.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER (PTSD): Police officers have been

long recognized as vulnerable to PTSD because of the long-term, violent, toxic environment in which they work. In some ways, a cop's work may be even more traumatic than that of a soldier sent into a war zone, says

clinical director Beverly Anderson. "The police officer's job, over many years, exposes and reexposes them to traumatic events that would make

anybody recoil in horror." Nonetheless, amazingly, there are some states that

refuse to recognize the existence of PTSD in police work.

In states that do recognize PTSD, challenges remain. Departments that

accept and validate an injury report for PTSD will then refuse to recognize the job relatedness of suicide by that same officer a week later, no matter how closely linked it is to the same traumatic incident on the job.

Three years of tracking has yet to reveal a suicide that has been recognized as “line of duty,” even though

several highly publicized cases are clearly such.

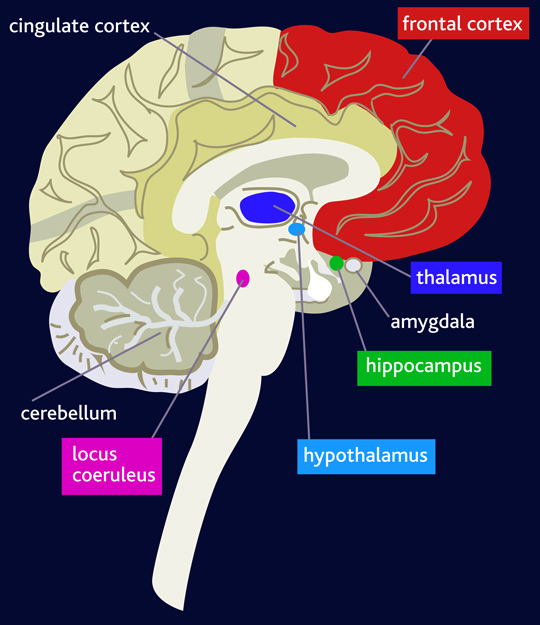

An abundance of literature is available about the impact a

traumatic incident has on the brain, thus leading to PTSD. Changes occur, both

physically and chemically, that are major and often long-lasting.

To date, there is no one medication available to treat PTSD, making control of the symptoms a confusing and sometimes

life-long battle.

THE “LINE OF DUTY” ISSUE:

There

is widespread confusion (and ignorance) about whether or not it is possible to be injured, both psychologically

and physically, in performing the police job and, if so, that such an injury (the classic example being posttraumatic stress

disorder) can lead to suicide. Much of this has to do with a lack of understanding

of the nature of PTSD itself. There are several key

points to remember:

- PTSD is clearly defined as an injury. It is not genetic. It is not a disease. It is the one and only psychiatric disorder in the Diagnostic

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) that is caused by an external source. It is not “caught,” and it is not the fault of the victim.

- Trauma:

The medical definition for “trauma,” which includes

“injury,” is “Any injury, whether physically or emotionally inflicted.” Trauma" has both a medical

and a psychiatric definition. Medically, "trauma" refers to a serious or critical bodily injury, wound, or shock. This definition

is often associated with trauma medicine practiced in emergency rooms and represents a popular view of

the term. In psychiatry, "trauma" has assumed a different meaning and refers to an experience that is emotionally painful,

distressful, or shocking, which often results in lasting mental and physical effects.

- PTSD is a physical injury to the brain—it is just as physical as a concussion and it is real.

- There are clear, measureable physical changes that immediately begin taking place to the hippocampus, which controls

learning, memory, stress and our emotional responses to fear. The hippocampus

actually decreases in mass and begins to atrophy.

b. The amygdala, the “fear center” of the brain, becomes overactive.

- “Those who have PTSD have abnormal levels of stress hormones. Studies

show that individuals with PTSD have lower levels of cortisol than those who do not have PTSD and higher than average levels

of epinephrine and norepinephrine. The above three mentioned hormones are responsible for creating the "flight or fight" response

to stress. In turn, this means that the person with PTSD lives in constant "flight or fight" mode.”

- Researchers believe that

the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates emotional and fear responses, becomes dysfunctional.

- Simply put, PTSD alters levels of numerous stress related chemicals and

hormones that would otherwise maintain emotional and decision-making balances in the brain.

This can easily trigger depression, commonly raising the likelihood of suicide.

- Richard Levenson, Psy.D., who specializes in anxiety and depressive disorders,

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and the effects of medical/physical conditions on psychological health and well-being. points out that “suicide with

many police officers is a function of a severe PTSD and depression. While this may be obvious to us, it is not to all.

We know that biological changes take place in the brain because medication reverses those changes, at least to some extent,

as it alleviates depression. However, severe depression can be hidden from others, and just because

a department command doesn’t see it, doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.”

- Memory, concentration and decision-making are impaired, having a clear

impact on the individual’s ability to make a sound "decision" about something like suicide.

It is understandably difficult for a “warrior culture” like law enforcement to accept that something “in

the mind” could be an injury. The prevailing thought is that the PTSD victim

should simply realize he is “in trouble,” see a counselor, take medications and “get better.” One, two and three. Would we ask the

same of an officer who has been beaten on the head by a suspect with a hammer? Of

course not. We can see the telltale signs of a concussion in the officer’s

eyes and gait and perhaps see blood. We will send him to the hospital and pray

for his survival. If he dies, no matter how much later, we will honor him and

place his name on a memorial wall as a hero.

If, however, that same officer makes a complete recovery from the concussive injuries but is psychologically traumatized

by the incident and commits suicide a few months later, we will bury him secretly without honors, refusing to recognize the

injury that killed him, and we will cast away his family in disgrace.

Not even his assailant is blamed for his death—this is suicide, and the victim as at fault.

What is confusing about PTSD is that the victim has no visible scar, does not limp and has no other visual signs of

injury. The victim acts and talks quite “normally.” This is not a gauge of how they are feeling inside with the injury, however, or the nightmares, flashbacks,

anxiety attacks and depression they are experiencing. Still, progress is being

made to recognize the role that stress and, more importantly, trauma can play in police suicides. Take for example:

- In 2010, at its conference, the International Association

of Chiefs of Police emphasized that stress in law enforcement can contribute to police suicide, even

presenting a class on how “how critical incidents and prolonged stress can affect and alter a law enforcement officer.” [italics ours]

- On the issue of “choice” in suicides,

John Violanti, PhD, a former NY state trooper and world renowned police mental health researcher at the University of NY at

Buffalo, stated in March, 2011,

“Advances in the understanding of the neurobiological

mechanisms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) suggest that inhibitory mechanisms that act to minimize distracting stimuli

and enhance attentional control may be disrupted in this disorder. Results suggest that there are disruptions in frontal attentional

brain mechanisms in police officers with high PTSD symptomatology. In short,” Violanti says, “frontal areas of the brain are responsible for reasoning and making decisions. PTSD impairs

this human ability. ‘Rational’ decisions are disrupted.”

- PTSD and depression have been recognized as co-occurrent. “Patients with at least one major depressive episode who

have or have had PTSD were significantly at greater risk of suicide attempts than patients with a major depressive episode

and no PTSD,” says Maria Oquendo, M.D.

- Compared to other anxiety disorders, persons with PTSD are high in risk

of anger impulsivity. Lack of impulse control is considered a key contributor to suicide (Brunner and Saddath).

SUMMARY – WE NEED TO RISE FROM THE MIDDLE AGES

The practice of “blaming the victim” in a suicide is an old one, going back to the Middle Ages and based

on a deep, visceral fear of suicide. Behind this fear is a deeply rooted

need to distance oneself from the act by proclaiming it to be shameful and even sinful act, dooming one for eternity and blackening

the family name forever.

We still practice this custom in the 21st century, but in more “sophisticated” ways. Rather

than burning down the victim’s home and family with it, we employ pseudo-scientific platitudes like, “Suicide

is a cowardly act,” or “Suicide is an angry act.”

This is fear at work. We don’t want to believe PTSD, depression

or suicide could happen to us. So we build up our defense like this: “Joe was

my comrade. I thought Joe was a hero. But

Joe committed suicide. Joe was weak and a coward. I am not weak or a coward like

Joe. Therefore I will not commit suicide.”

In spite of what Joe may have done in his life, our personal integrity is threatened by the mere thought of a police

officer (like us) committing suicide. We feel we must distance ourselves completely from anything associated with it. This includes the spouse and children who, after a few polite telephone calls, are

cast away from the police family as “untouchables.” The name of the

deceased officer, even the heroic deeds that may have driven him to suicide, are erased from memory. He is buried in near

secret and his name is forgotten, never to be seen in a place of honor for the sacrifice he made.

This must end. When an officer is injured while in the line of duty and dies of his wounds we must honor

him--not disgrace him.

There are pretenders to piety

as well as to courage. --Moliere

|

| Badge of Life Police Mental Health |

police stress managment police suicide police mental health police stress ptsd trauma badge of life mental

health check law enforcement emotional self care statistics officer suicide police peer support training therapy counseling

police suicides study studies NSOPS national numbers rate rates percent EAP employee assistance posttraumatic stress disorder

danger

stigma memorial

|